I'm Back With a Light Lesson

With the Perseid meteor shower approaching its peak, I thought it might be a good time to rant about light pollution.* Did anyone notice how wonderfully dark the sky was around here when most of the Quad City Area was without electricity? I'm not wishing another 100mph straight-line wind on anyone for Monday night, but maybe we could all do our little bit to make the night sky better for astronomical observing:

-Don't use more lights or brighter lights than you need at night. It doesn't take much to be able to see your way up the front steps.

-Don't leave the lights on longer than you need them. Please - no yard lights on all night long. If you are worried about trespassers and think light will deter them, use a motion-activated light. A dog works, too, right, Fred?

-Aim the lights where you need the light; don't send light out in all directions, including up toward the sky. Unless you are signalling ET.

So why does light aimed up at the sky cause a problem for us on the ground? For the same reason that the sky is blue and clouds are white. Most of the light aimed upward continues upward into space, as can be seen in satellite photos. But some of the light scatters from gas molecules of the air as well as particles such as dust. That scattered light gives you a "skyglow" that is very apparent above cities. My north sky glows quite noticeably from the Quad Cities 20 miles away.

How bad is skyglow? Check out this map modeling the skyglow in the northeastern US.

The white areas have close to ideal sky conditions. Only those areas and the two lightest shades of gray can hope to get a good view of the Milky Way or to ever see Uranus, even at its brightest. The darkest shaded areas on the map can only see three of the four stars in the bowl of the Little Dipper. Under ideal sky conditions, one can expect to see as many as 20 different stars in the Pleiades, whereas the darkest shaded areas will only see 6, even on a very good night. So much for the "Seven Sisters".

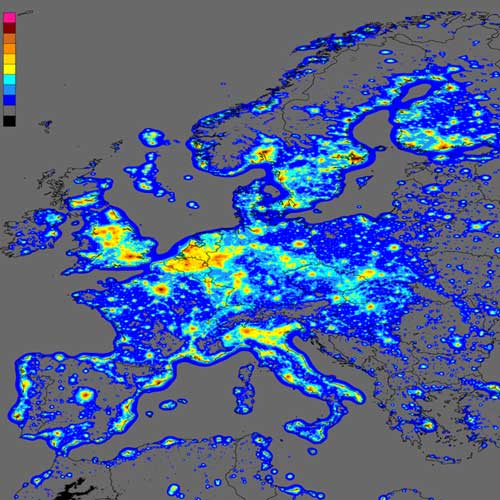

I guess it is even worse in Europe. Consider this map below, which is similar to that of the northeastern US, only more colorful.

Credit: P. Cinzano, F. Falchi (University of Padova), C. D. Elvidge (NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder). Copyright Royal Astronomical Society. Reproduced from the Monthly Notices of the RAS by permission of Blackwell Science.

In this map, the yellow areas (like the darkest areas in the US map) can only see three of the four stars in the bowl of the Little Dipper, but the red areas will be lucky to see three on a good night, and the violet regions can only see two!

Since this is a lesson, I should say a bit about the model used to produce these images. The model assumes that the light pollution due to a city is proportional to its population. Outside the city, the skyglow is assumed to fall off as (distance)-2.5. If it were just light travelling out in all directions unimpeded, it would be an inverse square law, or (distance)-2. Apparently, the power of 2.5 fits the data better. In "Light Pollution Handbook" By Kohei Narisada and Duco Schreuder, the authors guess that this might be due to light absorption (as opposed to scattering) in the atmosphere. It seems to me that light absorption should decrease the amount of light exponentially, rather than a power law. On the other hand, over the limited range of distances that this law is used for, a power law could surely be made to approximate an exponential times an inverse square. Fitting curves is awesome - as I'm sure you've heard, given enough free parameters, one can fit an elephant!

The model has been fit and verified for a variety of places, and then extrapolated to the rest. The model is certainly not perfect, as it leaves out factors that might be important such as

-density of population (in addition to size of population). The closer people live together, the more they can share the same streetlights.

-snow cover and other things that may affect reflection. Light aimed down might get reflected up.

-whether a city (such as San Jose, CA) has taken steps to lessen their impact on nearby astronomical observers (such as those at Lick Observatory)

-what else?

*Moonlight could be more problem than skyglow this year, but - oh, well, just stay out until it sets!

No comments:

Post a Comment